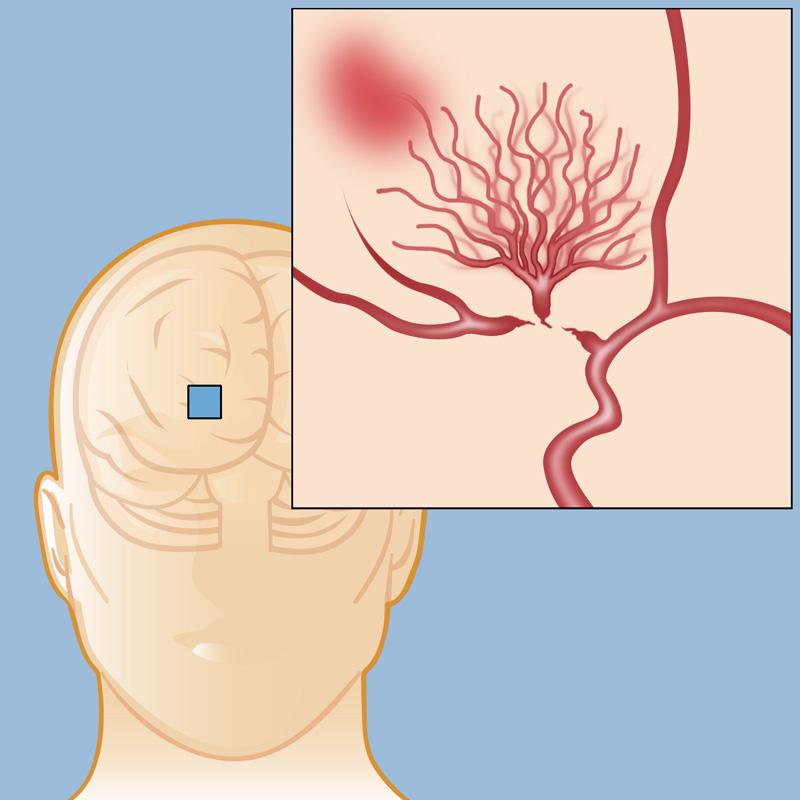

Moyamoya disease is a rare cerebrovascular disease characterized by the slow narrowing of major brain blood vessels over time, resulting in reduced blood flow to specific parts of the brain. With time, these changes may become severe and lead to ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, and seizures.

The Japanese doctors who discovered it named the condition moyamoya, which means “puff of smoke,” because of the way the network of tiny vessels that form at the base of the brain looks on imaging. Although it was first observed in Japan, the condition occurs worldwide.

Moyamoya affects both children and adults and may be passed down through families. There is no known medical cure, but surgical enhancement of blood flow to the brain may help.

Figure 1. Moyamoya disease

The incidence of moyamoya disease is most often during the first decade or fourth decade of life.

In general, the most frequent symptoms of moyamoya disease include:

- Weakness or numbness of the face, arm, or leg

- Difficulty speaking or comprehending speech

- Visual changes

- Headaches

- Seizures

- Balance difficulties

- Transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) or stroke-like symptoms that come and go off.

The typical symptoms in children are ischemic incidents, such as recurrent transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) or total strokes, that produce varied neurologic symptoms including weakness on one side of the body, sensory loss on one side of the body, vision problems, and speech disorders. These symptoms often come and go and are important to identify and seek treatment immediately.

If moyamoya disease is suspected, it’s critical to get a diagnosis and see a specialist as soon as possible. Physicians suspecting moyamoya disease will obtain imaging of the brain blood vessels as well as an MRI of the brain to look for abnormalities.

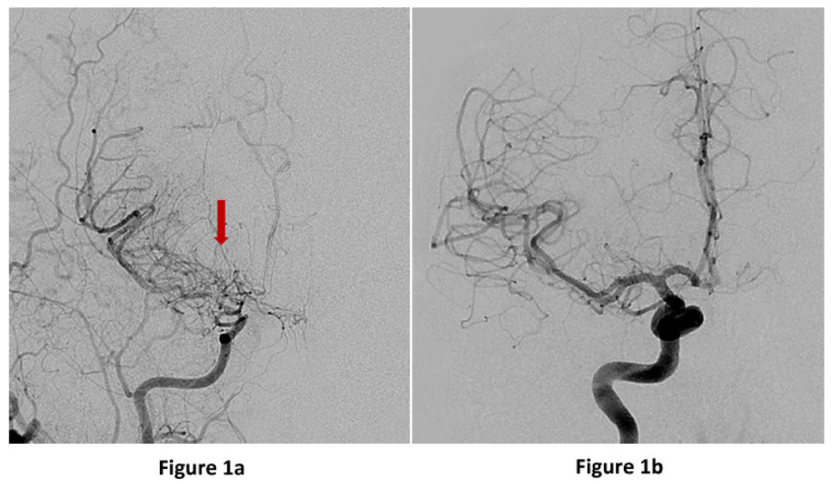

Angiography: The most detailed brain blood vessel imaging and is crucial for diagnosing and treatment planning for moyamoya.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Patients with moyamoya disease can have characteristic intracranial abnormalities that are visible on MRI studies. Magnetic resonance imaging is the most precise test to detect intracranial changes from moyamoya.

Neuropsychological assessment: Moyamoya disease significantly affects a person’s cognitive and day-to-day functioning. Executive functioning is most hampered. Memory and, to a great extent, intellect are unaffected.

Figure 2: Anterior or front view (image on the left) of a brain angiogram showing the right internal carotid artery narrowing into the small tangles of moyamoya “puff of smoke” vessels (red arrow). An anterior view of the right internal carotid artery cerebral angiogram showing a normal branching pattern for comparison (left).

Most patients with moyamoya disease will experience progressively narrowing brain arteries, reduced brain blood flow, and eventual ischemic strokes, mental degeneration, and possibly mortality from a cerebral haemorrhage.

Medical treatments for moyamoya disease include controlling seizures, ischemic stroke prevention and increasing blood flow to the brain. Blood thinners can help avoid vessel blockages and reduce symptoms but can also increase the risks in the event of bleeding. Cerebrovascular specialists will carefully assess each patient’s unique situation in recommending medications.

Surgical treatment for moyamoya disease can slow and even stop the condition from worsening by improving blood flow to the brain. Selecting patients who would benefit from surgery is nuanced and should be discussed with an experienced cerebrovascular neurosurgeon. There are two surgical strategies for increasing blood flow to the brain termed:

- Direct revascularization

- Indirect revascularization

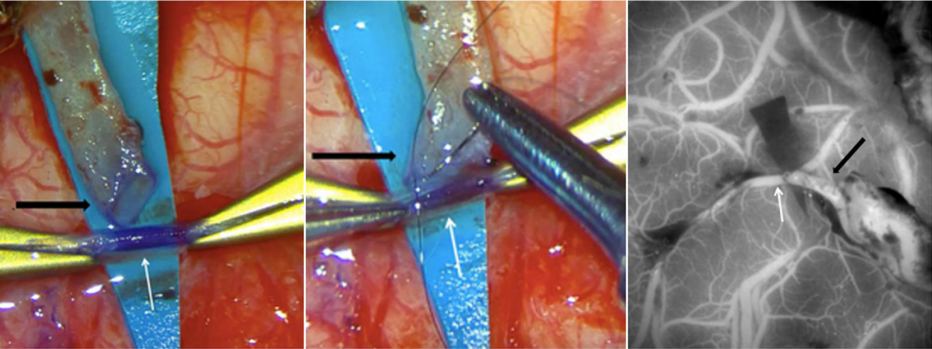

A direct revascularization, also known as STA-MCA bypass or EC-IC bypass, is an open surgical technique in which a blood vessel from the head (superficial temporal artery; STA) is cut and directly connected with a target vessel on the surface of the brain’s brain (middle cerebral artery or MCA).

By “bypassing” the blocked vessel at the base of the brain and creating a new blood flow pathway into the brain beyond the blockage, this operation increases blood flow to the brain right away. The sutured vessel continues to grow and deliver more blood throughout time.

Figure 3: Images from a STA-MCA bypass surgery showing (a) the cut STA (black arrow), which has been dissected from the scalp and trimmed in preparation for use as a bypass donor, and prepared suture into the brain MCA vessel (white arrow), (b) the open end of the STA (black arrow) is being sutured onto the open MCA vessel (white arrow) and (c) intraoperative ICG dye angiogram showing blood flow through the skin vessel (black arrow) into the brain vessel (white arrow).

There are several alternatives to a “passive” bypass that will aid in the circulation of blood to a moyamoya patient’s brain. The indirect techniques all require open surgery to implant healthy extracranial tissues with adequate blood supply on the surface of the brain, after which over time develop new arteries into the brain, providing much-needed extra blood flow.

These procedures are frequently utilized in children since the tiny blood vessels are difficult to manipulate with direct bypasses. Therefore, surgeons employ a variety of techniques, such as:

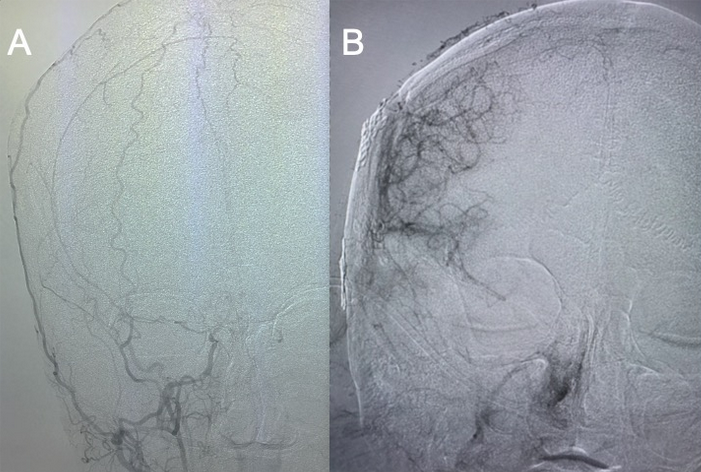

Encephalo-Duro-Arterio-Synangiosis (EDAS): The superficial temporal artery (STA) from the scalp is utilized in this most common indirect bypass. Rather than cutting and suturing the STA directly to the brain blood vessels, it is left intact and draped over the surface of the brain in this technique. With time, the vessel contributes new branches to the brain, which is essential for obtaining adequate blood flow. New blood vessel formation generally takes three to six months but may continue to improve over years.

Encephalo-Myo-Synangiosis (EMS): This is a similar technique to the EDAS. But in this procedure, the temporalis muscle – which is located above the skull near the temple – is inserted through an aperture in the skull and into the brain surface. New blood flow is established from muscular vessels to brain vessels after three to six months.

Encephaloduroarteriomyosynangiosis (EDAMS): This is a hybrid procedure that combines the EDAS and EMS techniques. The brain, dura, and muscle are all positioned on top of the brain’s surface.

Multiple Burr Holes: This is a surgical procedure that can be performed on infants and children. The small brains of children tend to grow new blood vessels from tiny regions of connection with extracranial tissues via many little holes drilled in the skull.

Omental Bypass: This surgical technique is unusual and is mostly done when alternative bypass techniques have proved ineffective. This procedure consists of removing fatty tissue from the abdomen and tunneling it underneath the skin, then transplanting it on to the surface of the brain. Vascularized fatty tissue with a blood supply from abdominal arteries may also grow new vessels into the brain.

Figure 4: A) Anterior or front view of the right external carotid artery supplying the skin and tissues of the head. B) One year after right EDAS surgery, an angiogram of the right external carotid artery now shows robust vessels supplying the right side of the brain.

Moyamoya is a slowly progressive process whereby major blood vessels in the brain narrow and small fine vessels termed collaterals form. However, the collateral vessels are fragile and may not provide enough blood flow to the brain putting patients at risk for ischemic strokes or bleeding into the brain. To determine whether a moyamoya patient may benefit from surgery, appropriate imaging studies and the patient’s individual symptoms should be reviewed with an expert cerebrovascular neurosurgeon.