Cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs) also known as “cavernous hemangiomas,” or simply “cavernomas” are clusters of closely packed abnormal blood vessels encircled by healthy brain tissue. These lesions range in size from less than a quarter of an inch to more than four inches. Unlike brain AVMs, these lesions are low pressure and low flow but still are at risk of leaking blood into the brain or spinal cord.

Figure 1. Cavernoma

It’s unclear what causes cavernomas, but 20% of cerebral cavernous malformations are associated with genetic modifications.

Cavernous malformations that are small and silent may produce no symptoms and remain that way. When symptoms do appear, they are generally linked to the development of seizure or a bleeding lesion.

The following are some of the more frequent symptoms connected with a cavernous malformation:

- Seizure

- Headache

- Weakness in the arm or leg

- Difficulty speaking

- Difficulty with balance

- Visual changes

Seek medical attention immediately if you are experiencing abrupt symptoms such as a severe headache, seizure, sudden limb weakness, or vision problems. If you’re discovered to have a cerebral cavernous malformation, you should be referred to a neurosurgeon.

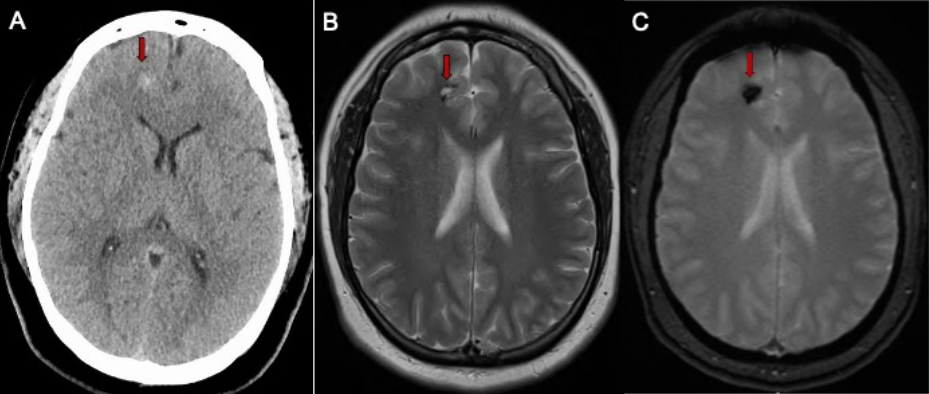

The most effective method to detect cavernous malformations is through magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans but other imaging studies may be needed to evaluate other characteristics of the brain and its blood vessels.

Computed Tomography Scan (CT): A CT scan is a computer reconstruction of a set of x-rays that doctors occasionally use to particularly determine whether a cavernous malformation has recently bled.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): An MRI scan uses magnetic waves to produce a more detailed image of the brain, can identify even very small cavernous malformations, and provides details regarding the location of the lesion within the brain. MRIs are often repeated and used to monitor cavernous malformations for growth.

Figure 2: A. CT scan of the brain in a patient with a mild headache showing a small spot of white bleeding (red arrow). B. Brain MRI scan showing a small cavernous malformation (red arrow) in the frontal lobe. C. GRE Brain MRI sequence confirms the presence of bleeding (red arrow).

Depending on a variety of criteria including the patient’s age, symptoms, number of cavernous malformations, lesion size or growth, position in the brain or spinal cord, proximity to other vascular structures, your cerebrovascular surgeon may advise waiting and watching the malformation or recommend surgical treatment.

Direct removal of the cavernous malformation with surgery is the only known cure. Surgery is often recommended for cavernous malformations that are causing symptoms, grow on repeat imaging and can be removed with low risk of harming the surrounding brain (Figure 2).

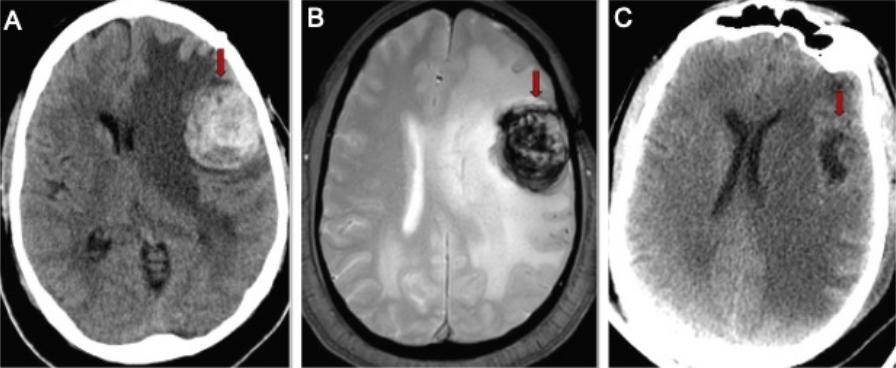

Cavernous malformations are surgically removed under general anesthesia in the operating room. The neurosurgeon locates the correct area of the brain using an intra-operative GPS system called stereotactic navigation. A small pathway is made through the bone over the malformation. The navigation system is used to pinpoint the lesion and the malformation is meticulously removed using an operative microscope. The goal is complete removal of the cavernous malformation with minimal disruption of surrounding brain tissue.

Figure 3. A. Brain CT scan in a patient having difficulty speaking shows a 3cm mass containing blood (red arrow). B. Brain MRI showing the mass with blood inside (red arrow). C. CT scan of the brain after surgery showing the cavernous malformation removed (red arrow) and less brain shift.

Surgery for cavernous malformations is best performed at specialized cerebrovascular centers like UCLA Ronald Reagan Medical Center where there are specially trained neurosurgeons, neuro-anesthesia and care in a specialized neurological intensive care unit. Patients are typically in the hospital for two to three days after surgery and length of recovery depends on the individual patient’s cavernous malformation.