Brain arteriovenous malformations, or AVMs, are abnormal clusters of blood vessels within the brain. They are thought to arise during brain development in utero or shortly after birth. In these malformations, there are unusual connections between arteries and veins, which over time can weaken and possibly rupture.

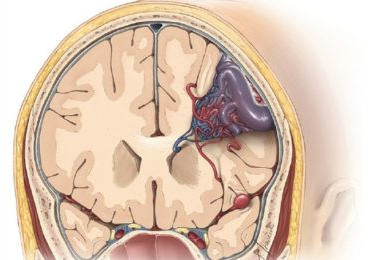

Figure 1. Brain AVM

An AVM is a collection of abnormal vessels with higher than usual blood flow, which over years can weaken and potentially rupture. If an AVM ruptures, blood escapes the vessels into the brain. Symptoms of a bleed may include body weakness, loss of speech, numbness, paralysis, coma, and even death. People with unruptured AVMs have an approximately two percent chance of the AVM bleeding each year. The goal of AVM treatment is to cure the AVM and prevent future brain bleeds. Each AVM is unique and management should be carefully discussed with a cerebrovascular professional.

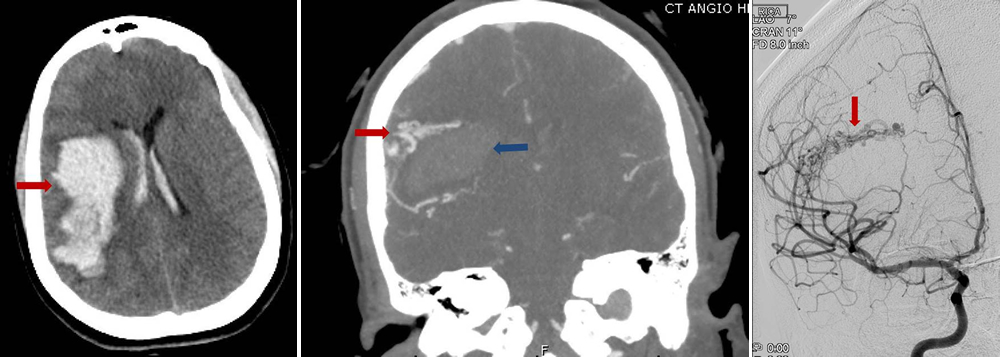

Figure 2: a) Brain CT scan showing bleeding (arrow) in the brain. b) CT angiogram showing bleeding in the brain (blue arrow) and nearby AVM vessels (red arrow) that caused the bleed c) Brain angiogram showing the abnormal vessel tangle (arrow).

The precise causes of brain AVM are unknown, but a majority are believed to form during fetal development.

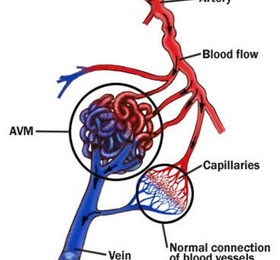

The brain receives oxygen-rich blood from the heart via tubes called arteries. Arteries divide into progressively smaller networks of vessels down to microscopic sizes tubes called capillaries. Capillaries then “trickle” oxygen to surrounding brain cells. Then, the blood passes through the capillaries into veins and finally back to the heart.

Unlike the normal brain vessel system, AVM arteries and veins don’t have a network of smaller capillary blood vessels between the artery and vein. In an AVM, the blood flows directly from the high flow artery directly to the vein which is not designed to handle high flow and pressure like arteries.

Figure 3. AVM abnormal connection between arteries and veins

Brain AVMs can happen in anyone, but they’re more common in males and in rare cases, they can be familial.

Unruptured brain arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are often silent for many years and cause no symptoms but are discovered when symptoms arise. About 50% of brain arteriovenous malformations are discovered when they bleed impacting the surrounding brain. Other AVMs are discovered when symptoms like seizures or severe headaches arise that cause doctors to obtain brain imaging. Symptoms after an AVM bleed vary depending on the location and size of the brain bleed. For example, cases of AVM rupture can result in severe headaches, weakness, numbness or paralysis, vision loss, difficulty speaking, confusion or inability to understand others, and severe unsteadiness.

There are three types of brain imaging tests that are used to evaluate the presence and location of brain AVMs:

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Uses a magnetic field to create and display images of blood vessels in the brain.

Computerized Tomography (CT) scan: Using multiple X-ray images taken from different angles the CT allows the doctor to see cross-sectional pictures of the brain and blood vessels. The contrast dye makes vessels more visible, it is often injected into an arm vein via an IV in order to get a better look at blood vessels.

Cerebral Angiogram (Digital Subtraction Angiography): Cerebral angiograms are the most accurate way to diagnose brain AVMs. During a cerebral angiogram, a small tubes is introduced into the arm or leg artery, advanced inside the blood vessels under x-ray guidance. Contrast dye is injected through the tubes into the blood vessels where it travels with blood flow towards the head and fills the brain vessels while images are obtained demonstrating the blood vessels in excellent detail.

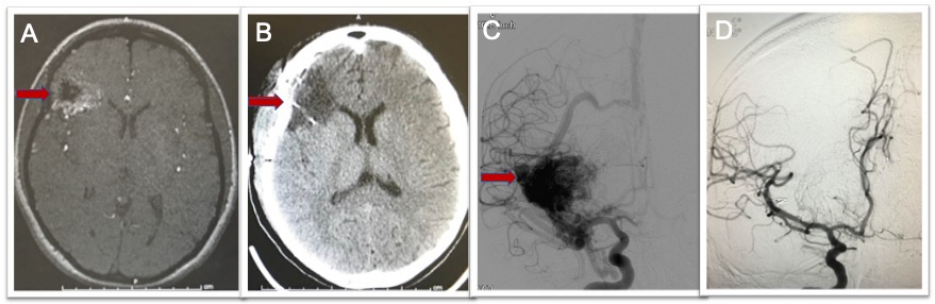

Figure 4. Brain AVM imaging techniques. A) MRI scan showing right frontal AVM (arrow). B) CT scan after surgery showing no remaining AVM. C) Brain angiogram before surgery showing the brain blood vessels and large AVM (arrow). D) Brain angiogram after surgery showing no remaining AVM and normal vessels filling.

There are several factors a cerebrovascular neurosurgeon will consider when deciding whether to treat a brain AVM, including the size of the AVM and where it’s located as well as a history of prior AVM bleeding into the brain.

There are three treatment tools available for AVMs:

- Microsurgical Resection

- Endovascular Embolization

- Stereotactic Radiosurgery

Microsurgical resection is often the best option for AVMs located in favorable areas of the brain because it allows for the immediate and complete cure of the AVM, with a good safety profile. For this treatment, the patient undergoes traditional surgery in the operating room and an angiogram during surgery may be used to confirm that the AVM is removed completely (Figure 5).

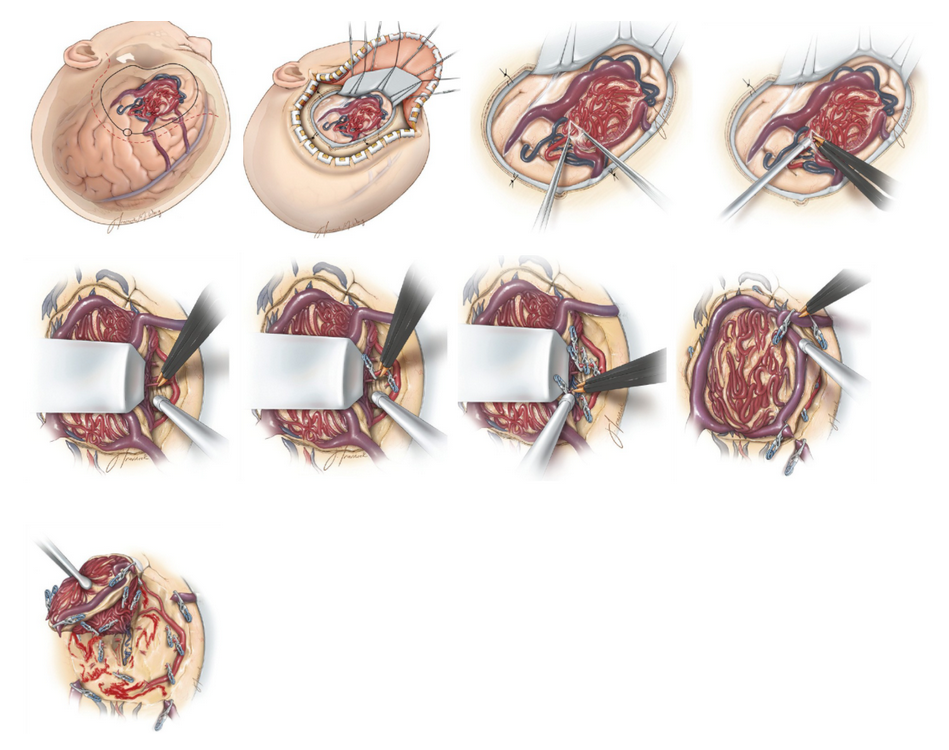

Figure 5. Microsurgical Resection of an AVM. a) Incision and craniotomy for generous exposure of a left frontal AVM. b) Intradural view of a left-sided frontal convexity AVM. c) Arachnoid membranes covering the AVM are often thickened and should be generously dissected open to allow for clear identification of margins of the AVM’s free surface and surrounding vessels. d) A surface arterial feeder is identified and occluded using bipolar electrocautery. e) A length of the artery is dissected out and some of the more superficial ones may be occluded with bipolar coagulation. f) Deep arterial feeders may be clipped and divided as they do not easily occlude with bipolar coagulation. g) Parenchymal dissection and division of deep arterial feeders proceed toward the ventricle. h) After all arterial feeders are occluded, the primary draining vein is clipped, coagulated, and transected. i) The AVM is removed from the resection cavity, which is inspected for any persistent bleeding.

It is rare to cure an AVM with embolization alone. Embolization is often used prior to neurosurgery to decrease the blood flow in the AVM, making neurosurgery safer. The embolization procedure is performed by feeding small flexible tubes into the arteries of the brain, using x-ray guidance, and once inside the AVM, a liquid glue is injected into the AVM vessels which blocks blood flow through them.

Stereotactic radiosurgery, also known as radiosurgery, involves aiming multiple focused beams of radiation that converge at the AVM. Ultimately, a signifiant dose of radiation is absorbed by the AVM, but very little radiation is absorbed by the surrounding brain. Over time, this radiation exposure narrows and shrinks the AVM blood vessels until they go away. However, the downside of this treatment is that it may take two to three years for the AVM vessels to shrink away, and during this time, there is still a risk of bleeding. Furthermore, only approximately 70-80 percent of patients are ultimately cured with this technique.

Brain AVMs are nuanced lesions and AVM patients should be evaluated by a cerebrovascular expert who can obtain appropriate imaging studies, interpret the results and discuss the management options as well as evidence based recommendations.